Earlier this week, writer Helen Donahue discovered that artist Andrea Bowers had included images of her bruised face, collarbone, and shoulders in Open Secret, currently on view at Art Basel. Donahue had not been consulted about Bowers’ use of the image, and sought help from followers on Twitter to have the image removed from the artwork.

cool that my fucking photos and trauma are heading art basel thx for exploiting us for “art” ANDREA BOWERS @unavailabl DO YOU KNOW HOW FUCKING INSANE IT IS TO FIND OUT MY BEAT UP FACE AND BODY ARE ON DISPLAY AS ART RN FOR RICH PPL TO GAWK AT THRU A STRANGER’S INSTAGRAM STORY pic.twitter.com/5X9vF5hZE5

— helen (@helen) June 11, 2019

Unlike most disagreements about appropriated imagery, this one was resolved quickly. Bowers removed Donohue’s photograph from the installation and publicly apologized to Donahue via Artnet, contacted her privately, and acceded to her wish to have the image removed from display. I see this as the best possible outcome, but am also sensitive to the way that this resolution abruptly truncated public conversation about Bowers’ appropriation of Donahue’s photograph.

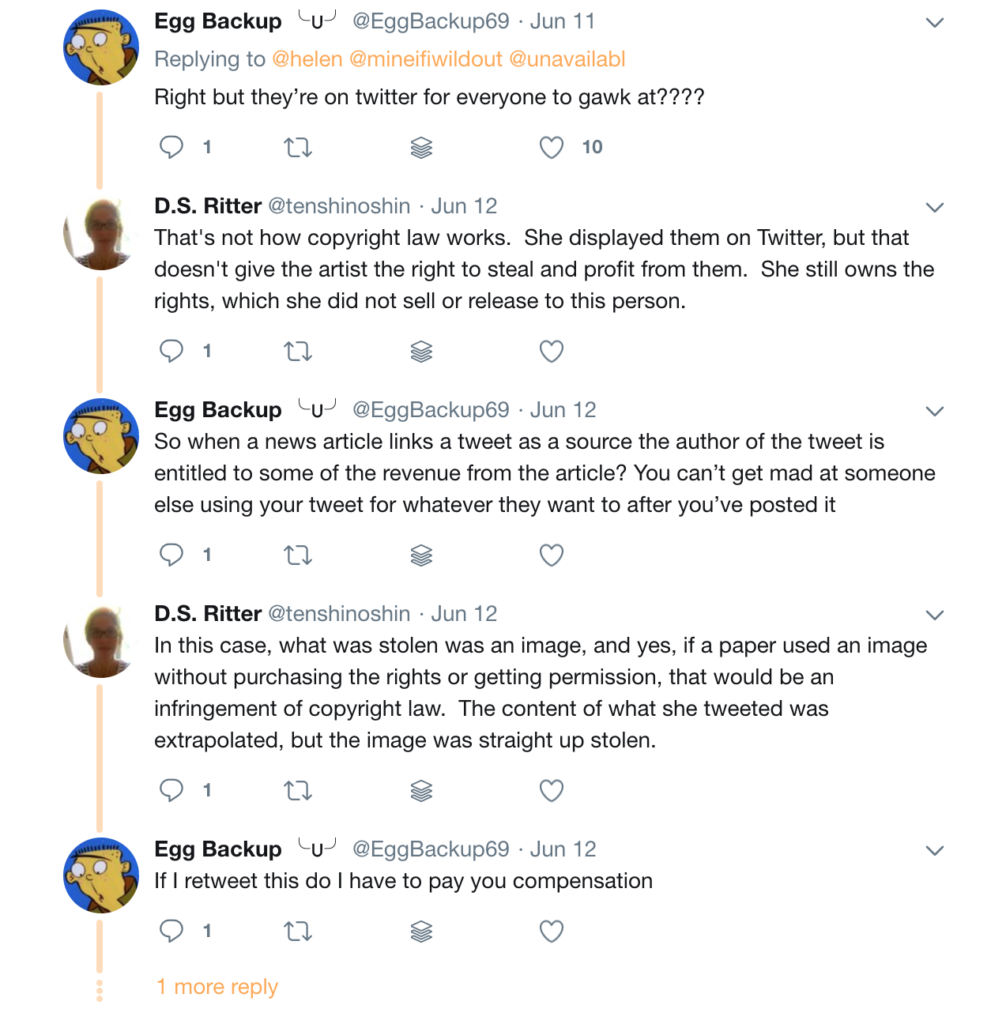

Open Secret raised a number of legal and ethical questions common to appropriation artworks that address social, political, or emotional issues. Bowers’ swift response left most of these questions unanswered. So many unresolved questions leave lots of misinformation floating around on the internet, furthering confusion about copyright basics.

(Note: Photographs repurposed for news reporting are rarely held to be copyright infringement.)

Short answers to obvious questions:

Is it copyrightable?

Yes.

Is it Donahue’s copyright?

If Donahue took the photo, it’s her work of authorship. If another photographer took the photo, the copyright belongs to that photographer and Donohue is merely the subject (absent an agreement to the contrary).

Could Donahue sue?

If Donahue obtained a copyright registration in the photograph, she may immediatelyfile a claim for infringement in federal court. If she didn’t, then she’ll need to apply for said registration before she can file suit. Same for a different photographer.

This is an area of great confusion online. Half the tweets you read will say “Sue ‘em!”

and the other half will say “It’s online so anyone can use it!”

Or my favorite: “It’s in the public domain!”

Did Andrea Bowers do anything wrong?

Bowers reproduced the photograph on Donahue’s Twitter feed without permission from the photographer. That’s infringement. Fair use – which is a defense to copyright infringement, not a coterminous right – is the obvious rebuttal here.

Is it fair use? Fair use is determined by a context-specific four-part balancing test. The bulk of the parties’ arguments in a hypothetical lawsuit would be the “transformativeness” of the work.

It’s a highly text-based work that requires close analysis to determine the extent to which Donahue’s image was transformed.

I haven’t seen the work in person, or even good photographs of it. I simply can’t know.

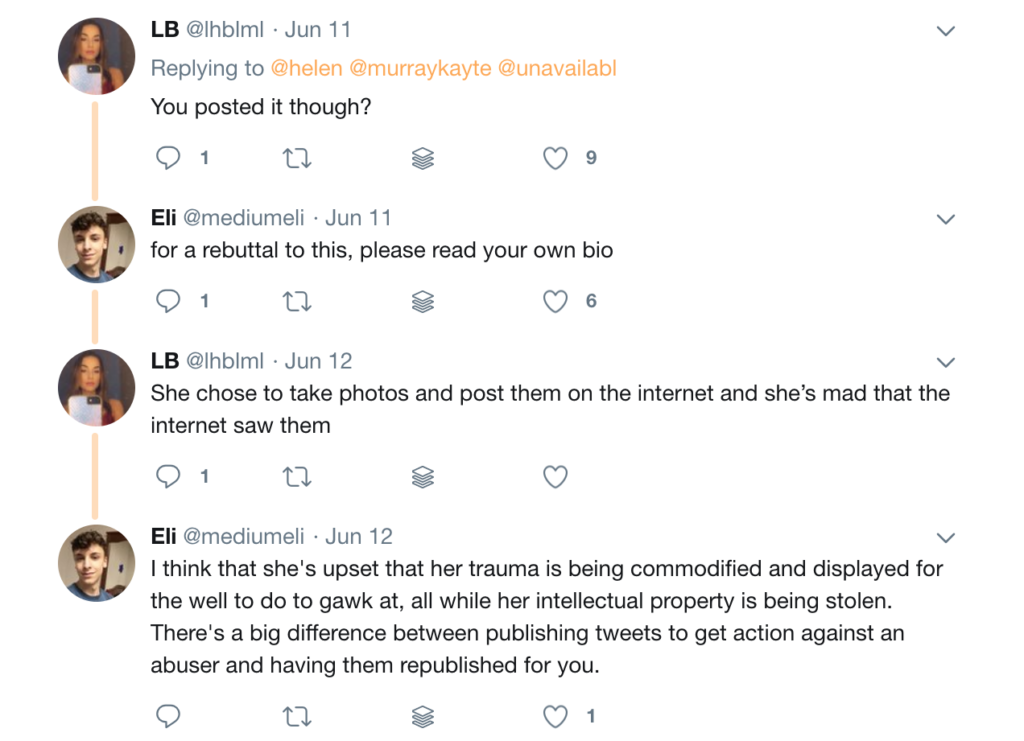

Ethically, it was highly questionable. Using images of or created by abused women in an artwork about abused without the permission of said women defies logic and feeling. An artwork may be brilliantly transformative, but that only makes it legally acceptable, not ethically sound.

Whenever we reuse images, we need to consider not only the legality of our decisions, but also the impact of our decisions on the makers of these images. Impact may be a financial or practical question – but it is always an ethical question.

Recirculating a record of trauma without the traumatized person’s consent – regardless of the traumatized person’s own use of the image – is a reasonably obvious ethical violation.

View this post on InstagramA post shared by Andrew Kreps Gallery (@andrewkrepsgallery) on

Did Art Basel, galleries representing Bowers (Andrew Kreps, Kaufmann Repetto, Vielmetter Los Angeles, and Capitain Petzel) and curator Gianni Jetzer do anything wrong?

Depending on their level and kind of involvement, Donahue might have a claim for contributory infringement. Contributory infringement applies when a person or company may be held liable for infringement even though he or it did not perform the infringing activity. It attaches when the person or corporation induces or authorizes the infringer to infringe.

For example, in Cariou v. Prince, Patrick Cariou sued Richard Prince and Gagosian Gallery for copyright infringement. Gagosian was potentially liable for reproducing Cariou’s photographs in exhibition catalogs, advertising, and paper ephemera related to its exhibition of Prince’s paintings, as well as the exhibition itself, which marketed the works for sale.

A decision to exhibit and promote Open Secret is considerably less surprising than Bowers’ decision to include Donahue’s image. These actors operated at a remove and likely weren’t considering potential liability.

When Andrew Kreps gallery staff is preparing brochures and Instagram posts to promote an exhibition, and marketing the artwork to potential buyers, it isn’t thinking about contributory infringement. We don’t want them to – they’re not experts. The gallery’s legal team takes on this consideration – and we don’t want them reviewing each artwork!

This is why many exhibition contracts include boilerplate language about artist liability for the use of copyrighted imagery. Such clauses shift risk to the artist and attempt to mitigate possible liability for the company.

More questions? Comment below.

—

Further Reading:

Following Social Media Criticism, #MeToo Artwork at Art Basel Removes Image of Assault Victim